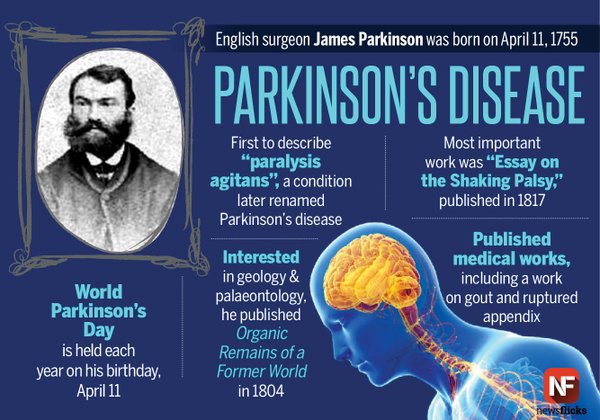

2017 marks the 200th anniversary of James Parkinson’s description of the disease that now bears his name and that affects an estimated 5 million people worldwide. Working as a medical surgeon in London, James Parkinson was the first to connect the dots when confronted with a handful of patients with similar involuntary tremors and symptoms of muscle weakness. In 1817, he published his findings in his seminal ‘Essay on shaking palsy’.

Parkinson’s disease and the search for a cure

Over the following century, many neurologists contributed to a better understanding of ‘shaking palsy’. One of the most important figures was Jean-Martin Charcot. He differentiated rigidity from weakness and slow movement, and recognised that the disease was slightly more common in men. Charcot was also the one who proposed the name Parkinson’s disease (another neuronal disorder, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, would later be named after him). In terms of treatment, Charcot used anticholinergic inhibitors, which—as we now know—influence the balance of cholinergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitters in the brain. Yet, it would take until the 1960s for the first (and still best available) drug for Parkinson’s disease to be developed. The dopamine precursor L-dopa entered clinical practice in 1967, exactly 50 years ago. It serves as a symptomatic treatment only, replenishing dopamine levels in the brain to temporarily compensate for the progressive loss off dopamine-producing neurons.

Fast Forward to 2017

Today, we understand quite well how the loss of dopamine-producing neurons leads to the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but we still don’t know why exactly these neurons die. Yet, we have reason to be optimistic: step-by-step we uncover new insights into the disease mechanisms. Over the past two decades, genetic studies pinpointed several genes and cellular pathways that play roles in disease onset and progression.

Looking ahead

April 11th, James Parkinson’s birthday, is World Parkinson’s Day. Each year in April, thousands of people across the globe roll up their sleeves to raise awareness for the disease and the consequences for all those affected by it.

We have come a long way since the publication of ‘Essay on shaking palsy’, but we haven’t found what James Parkinson was looking for: a way to stop the disease in its tracks. We’ll continue working until we do.